I’ll admit that a tweet I sent a few days ago was intended to be provocative. I was commenting on the rapidly-heating place of religion in this year’s elections. As usual, my focus was on the way media are involved in shaping the understanding and the effects of religion.

And, there’s been a lot to write about. There’s religion in the QAnon movement, religion in the way the press are covering the Biden-Harris ticket, religion in Trump’s ongoing cultivation of his base. I’ve got some upcoming entries on these things. But for now, my intentional indiscretion.

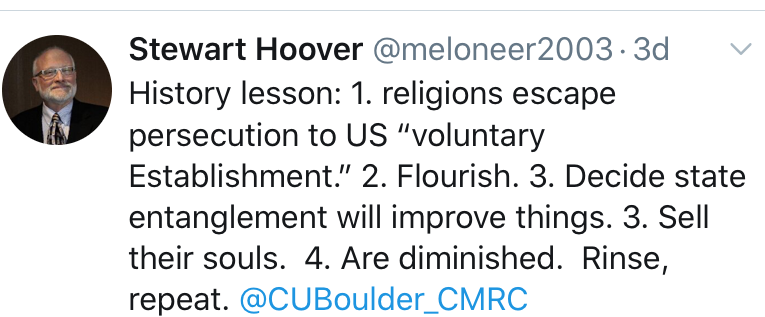

It started with the tweet to the right. In it, I noted the provenance of the public and mediated projects of today’s odd coalition of conservative Catholics and evangelical Protestants. Others can mentally footnote the deep history of animosity between these groups in the US. That rift has been conveniently glossed over in the Trump era. But it reveals the dynamic history I detail here.

Religions that fled persecution in Europe to the free atmosphere of the “New World,” get established, and then decide that state entanglement isn’t such a bad thing after all, as long as they get to do the entangling. Yes, in the guise of today’s patently contradictory “religious liberty” discourse, they claim to be asking only to be ”left alone.” But that’s not the effect of things like the Masterpiece Cakeshop and Little Sisters of the Poor SCOTUS decisions. Each shifted the balance away from religious freedom and toward religious standards for public accommodation. A very dangerous direction. And it is a direction that runs risks for these movements themselves.

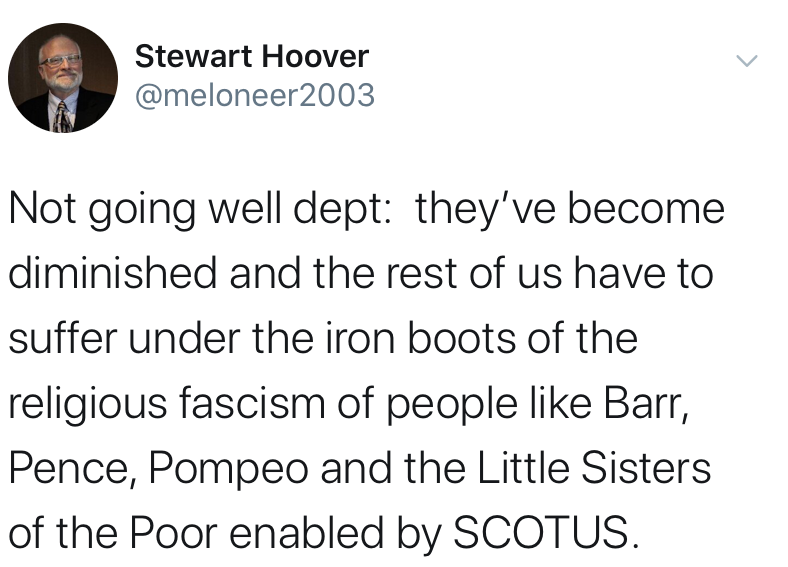

The outcome, in our present case, is as I described in my scandalous tweet (below). In it, I tied together several public faces of these efforts to re-center religion as a definitive locus of power in the culture. (I refer you to my earlier blog post “Culture is Everything” for the outlines of why I use the term “culture” the way I do.) I specifically noted figures in the Trump administration, and–for good measure–the poor little Little Sisters of the Poor.

In an excellent and probing legal analysis, Linda Greenhouse of the New York Times unpacked what could be read as either the wonderful coincidence or the disingenuous cynicism of their participation as a plaintiff in the anti-ACA cases at the court. As she notes, one couldn’t ask for a more sympathetic nom de guerre than “Little Sisters of the Poor.” In a single trope, their name is able to invoke a whole superstructure of sympathetic cultural memory of the (often under-appreciated by Church authorities) good works of women religious (a history I readily grant and celebrate, of course). It elides that they are also a multi-national health-care system supported by wealthy donors with deep pockets and vast resources.

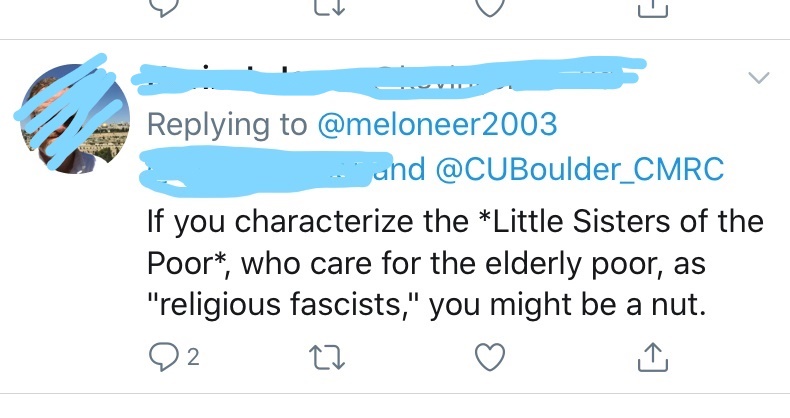

As a “brand” they got what they wanted. Justice Alito waxed poetic about their good works. But, as Greenhouse suggests, their “brand” has enduring, powerful, cultural “legs.” This was amply demonstrated by the first response I got to my tweet, which you can see below.

There are several frames to the involvement of the Little Sisters in this affair. Yes, they saw themselves as faithful stewards of Catholic social teaching in their obsessive moralism around the act of registering with their insurance company (we could talk for hours about the parallels to the equally-valid faith-based objections to draft registration or to taxpayer support of capital punishment, but that’s for another day). Yes, their claims were judged by SCOTUS and that frame was straightforward and resulted in a judgement that I consider to be very ominous for Establishment Clause (remember that?) principles. But the third frame is the one that caught me (as I knew it would). The “brand” represented by the Little Sisters worked exceptionally well to condition the discourse around their case. Exhibit A: the facile and blithe way in which my correspondent on Twitter was, with great confidence, able to pronounce me “…a nut.”

Well, I am not a nut. What I am is an observer of contemporary religion, media, and politics, and I can see in the trends represented by the “religious liberty” advocacy in contemporary politics the dark portent of religious oppression in reverse. And it is fascistic in some regards, in that it represents a desire to impose on a free society a regime where a religious test trumps all else. Public accommodation, which should be the fruit of a society truly committed to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, is giving way. We are seeing a relentless assault on those values by those who think religion is somehow disadvantaged when it is required to submit itself to a larger democratic good. They are for the moment ascendant.

Leave a comment

Comments feed for this article