As we move further from the events of September 6, and with the inauguration of the new President also in the rearview mirror, but with Republican Party politics still pulsing with the consequences of both, some interesting developments directly relate to the argument I’ve been making in this series of posts. Reports have surfaced that the radical masculinist “Proud Boys” are beginning to re-think their identification of Trump as a model of manly political purpose. We’ve also seen that the cultic, quasi-religious “Q-Anon” community has begun to suffer the pangs of doubt that emerge “when prophecy fails.” And, the so-called “Q-Anon Shaman,” identified around the world as a horned and pelted symbol of the capitol siege, has begun to feel that he was misled and lied to.

On the one hand, these developments point to the dimension I emphasized in my first post in this series: the seeming ephemerality and superficiality of these moods, movements, and gestures. They illustrate a seeming contradiction: Anna Surbrey’s (see post 1) point that these protests are “de-coupled from the real world,” that the rioters seemed at the same time aimless and deeply dangerous. On the other hand, though, they were actually, empirically dangerous and engaged in acts of violence, even sedition. The ludic playfulness of the memes, the “lulz,” and the connotative appropriations masked their potential to be brought into being in actual acts of purpose in physical and social space.

Up to now, I’ve argued that the material culture of the emergent politicized religion of the right emerges out of a number of sources, but is made possible by its instantiation at the level of the imagination in media (mostly digital-media) circulations. I’ve also suggested that the driving logics are derived from a religious-nationalist impulse that has deep roots and broad expressions across a range of very contemporary cultural contexts (expressing itself today from the US to Russia, to Brazil, to India, etc., etc.) I’ve further suggested that its roots in the U.S. context in particular can be traced through a long provenance of racialized far right nationalist politics, and that that history has been specifically shaped by its interaction with mediated conservative Protestantism, including the televangelism of the 1970s and 1980s. This history also—not incidentally—includes the development late in the last century of masculinist militia movements that see themselves as its active edge.

And what are the particular claims, projects, and goals? As I’ve noted in my last post and elsewhere, we can see three broad dimensions to the current religious-nationalist cultural battle. First, a deep and abiding nostalgia for dimly remembered and lamented pasts. Second, an absolutist commitment to rhetorical and embodied returns to a traditionalist racial and gendered domestic sphere. Third, almost irrespective of but certainly independent from these other two, an absolute commitment to “re-marking” the public sphere with religion.

Now, to the question of how we think about these “signs and wonders.” This is a phrase that I use both advisedly and deliberately. It has Biblical sources (originating in the book of Exodus) and has become coded language to describe transcendent and esoteric evidence that has powerful capacities but carries with it the implication that it must be properly read and interpreted. Signs and wonders are—in communication theory terms—equivocal. I want to use this framing for the evidence I’ll discuss here as I want it to be understood in this way, as connotative and appropriative symbolic gestures. We should not be looking for definitive grounding in these signs themselves but understand them as they are invoked, deployed, interpreted, and used by these various interest groups. What we are seeing are expressions of politics that can become materialized within various “interpretive communities.”

I want to treat these things as evidence in their own terms, asking the question “evidence of what?” And, more importantly, as one of my teachers once said, “…it is not a question of what is happening as much as a question of where it is happening….” So, where are these things happening? Who cares about them? What historical or moral or value trajectories do they represent or inhabit?

We should also not forget that these “signs and wonders” are imaginaries that have become portentously real. They are made possible, rendered plausible, exist, become material, and are circulated to their adherents and to us, by media. They are media phenomena.

But, they are also religious phenomena. The realization of this has grown both within and beyond mainstream journalism. A recent essay in The Chronicle of Higher Education, by Jacques Berlinerblau brought this home in ham-handed detail. It stoked a controversy because of its preposterous claim that religion scholars have overlooked the rise of religiously-inflected militancy on the right and should have warned everyone. I’ll only note that Berlinerblau must not have been paying attention. I and scores of others have been looking at and writing about this for years (here is a very current example that appeared in the NYT). But nonetheless, the fact that a prominent scholar could feel empowered to make such a claim, and that the Chronicle would publish it, shows in no uncertain terms that the roiling cultural production circulating in our hypermediated public sphere has caught a lot of attention, and that it is obvious that to understand it, we need to understand the religion, and the media, in it.

And it is all quite confusing, both to lay observers, and as Berlinerblau inadvertently demonstrates, to scholars alike. This is largely due to their desire to describe religion in traditional institutional terms, where its roots and sources in history and doctrine are thought to define it, and that the story of modernity is the story of its secularization. Conversely, those of us who follow the contemporary circulations and evolutions of religion, particularly as it has become so much an expression of and in modern media, understand that we’ve got to look elsewhere to understand it.

The elastic fungibility of these signs and wonders and their adaptability to new streams of thought and action unfolds before our eyes in real time. We’ve lately learned that the quasi-cultic, quasi-rational Q-Anon movement is confronting its disillusionment with the election by generating new networks as well as new arguments and new symbols to account for the failure of its prophecy. The masculinist militants who have sought to enforce the interests of white Christian nationalism are also searching for new grounding in the post-Trump era. In the “real world” of religious authority as well, some re-thinking is underway with some voices in his Evangelical base beginning to question their support of him.

In the swirling realities of this field of meaning-making, we have to understand that the “religion” in it is hypermediated religion, and that makes hard definitions and taxonomies difficult. In order to account for all of this we need to begin by reading contemporary geographies through these signs and wonders. That is because, in the main, they are where the real cultural work is being done. Trajectories of history, doctrine, experience, and even faith and belief, flow into and out of the systems of cultural expression in which and through which we can come to terms with mediated religion in contemporary politics.

To get scholarly-wonkish for a moment, what I am advocating for, I think, is actually a particular method, where we read into and out of these signs and wonders, generating new insights into their sources, their settled and contested meanings, their aspirations. We want to find out, to paraphrase WJT Mitchell, “what they want” from us, from their own interpretive communities and networks and from broader social and political histories and contexts.

Among the evolving meaning systems that have circulated in the events of January 6, there are three that I have been following with particular interest. Readers may have their own, but these are mine. I present each as a provocation. I am not nearly done with analyzing them, so this is work-in-progress.

Emerging fields of imaginative religious struggle

I’ll point to two quite distinct trajectories. First, there are the symbols, practices and claims that appear homologous to or bear a “family resemblance” to religion. Q-Anon and Trump networks seem to be like “cults,” and their adherents “believers.” In another time, these could be dismissed as mere appropriations of the banal and familiar categories of belief and identity. Today, though, these seemingly superficial gestures have crossed an important line into the geography of religiously-structured meaning making. This is illustrated in Jeff Sharlet’s superb journalism on Trump supporters. In an August 2020 piece in Vanity Fair, for example, he described the emergence of what he identified as a “new Gnosticism” among his informants. They derive vital emotional and cognitive energy from believing that they are part of a special, set-apart group, who have access to deep, hidden truths and esoteric knowledge. In their view, Trump is a particular avatar of that knowledge, and even his most nonsensical utterances and tweets actually hold deep, systemic meanings, as long as you know the code. As Sharlet notes, this sensibility has historical roots, but is comfortably embedded in certain strains of American religion, specifically Christian Pentecostalism: the “prosperity” gospel of most of Trump’s “religious cabinet,”

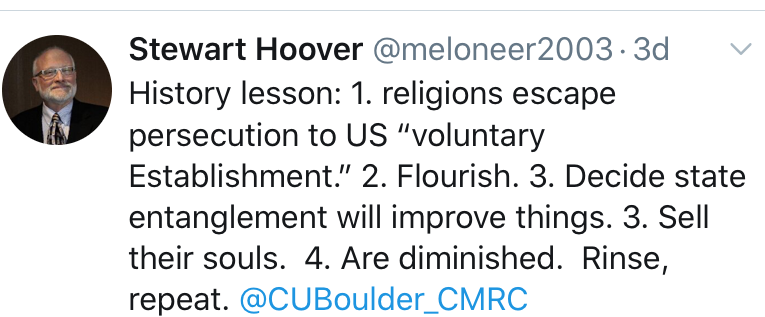

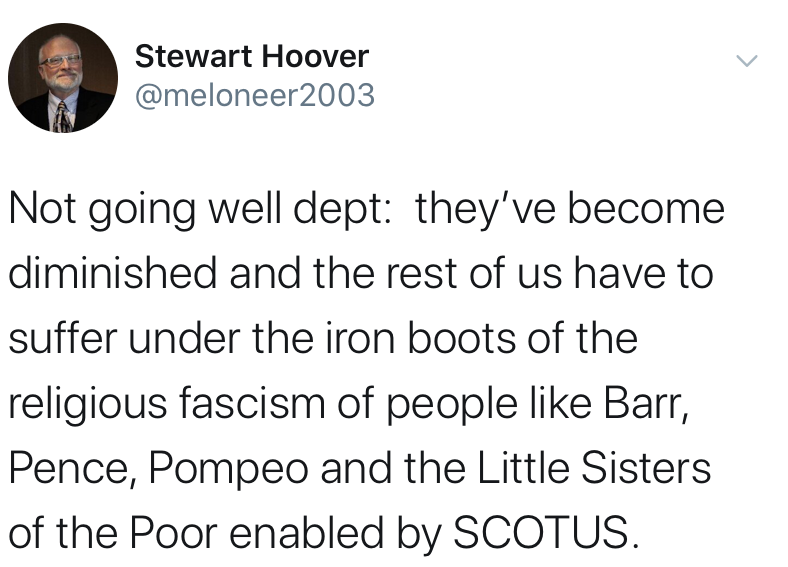

Against the religious homology of Sharlet’s neo-Gnosticism has emerged a set of interests more sedimented in contemporary struggles over institutional authority, tradition, and power. And indeed a number of key figures in the Trump orbit, and a broader network of interests they represent, adhere to an evolving conservative, even revanchist, view of the role of government. I’ve described several of these figures and their associations here. Robert Barr, Pat Cippilone, Mike Pompeo, Kayliegh McAnany, and others see their role in government as placing them where they can achieve the religious-nationalist objective I mentioned earlier: re-marking the culture with religion. In the latter part of 2020, both Barr and Pompeo made public statements that suggested they see contemporary politics as a battle between a true Christian national project and the dark forces of secular humanism, relativisim, and socialist atheism.

This view has also been articulated by Senator Josh Hawley, who became a central figure in Trump’s efforts to overturn the election. In a Washington Post profile of Hawley, we can see the core of his view on religion-state relations. “The mission of the state is to secure justice,” Hawley wrote. “Justice, as it turns out, is the social manifestation of the kingdom.” The accomplished interpreter of contemporary religion and politics Katherine Stewart described Hawley’s views in depth in the New York Times. Stewart shows that Hawley’s religion-politics vision is driven by a desire to turn public culture and the state away from contemporary forms of Palagianism. Palagius was an early-Christian figure who advocated an ethics rooted in a kind of relativism or situationism. Stewart notes,

In a 2019 commencement address at the King’s College, a small conservative Christian college devoted to “a biblical worldview,” Mr. Hawley denounced Pelagius for teaching that human beings have the freedom to choose how they live their lives and that grace comes to those who do good things, as opposed to those who believe the right doctrines.

According to Stewart, Hawley went on to cite Justice Anthony Kennedy’s words from the 1992 Casey decision as particular and influential examples of the stain of Pelagianism in contemporary life.

“At the heart of liberty,” Justice Kennedy wrote, “is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.” The fifth-century church fathers were right to condemn this terrifying variety of heresy, Mr. Hawley argued: “Replacing it and repairing the harm it has caused is one of the challenges of our day.”

The notion is that there is a dark battle underway for the soul of the nation, coded as a struggle to re-inscribe the nation and the culture with markings of a particular relationship between religion and the state. Against the separationist view of the First Amendment (generally understood be the view of the founders themselves), these voices wish religion to be restored to a rightful place at the center of the national culture and the state. In this, Hawley joins not only Barr and Pompeo but also Steve Bannon, who is increasingly known for his theological and political activism pointed toward creating a new and more militant Catholicism. And, of course, Bannon is significant to my project here for the fact that he has been an important producer of media (“affective infrastructures”) directed at this project.

The linkage between Catholic and Protestant interests is profoundly important. Most observers have noted with interest the joint project around reproductive rights that has linked conservative Catholics and Protestants. This larger—and far more important—project of recovery of lost pasts against the challenges of modernity, has been largely overlooked. In a trenchant analysis published in La Civlita Catolica in 2017, Antonio Spadero and Marcelo Figueroa described a much deeper historical and moral linkage. They describe the similarities and the roots in history that link Protestant Dominionism and Catholic Integralism. The two are linked by shared history, and a share sense of nostalgia and grievance. Simply put, they share much more in common than a joint opposition to abortion rights. Echoing my thesis regarding the project of religious nationalism today, they agree on their shared nostalgia, a shared project of recovering a traditional gendered and racialized public sphere, and on a shared project of re-marking the public sphere with religion.

So at the risk of over-simplification, we might say that the emergent religious landscape can be seen as a field of struggle where two streams of media-generated religious impulse are emerging. One of these is the neo-Gnostic, esoteric circulations represented by Q-Anon: esoteric and anti-authority forces seeking and finding imaginative signs and wonders in the material struggles of contemporary cultural politics. The other is the Integralist or anti-pelagianist stream represented by Hawley, Bannon, Pompeo, and by a newly-formed populist think-tank called The Center for American Restoration.

Again, these two streams do share in common the deep geography I described earlier…the desire of a restoration focused along dimensions of nostalgic grievance, of recovery of a racialized and gendered “normalcy,” and of a re-marking of culture.

One can only wonder, incidentally, what this all might mean for the Roberts Supreme Court as it considers inevitable “religious liberty” cases.

For my project here, it is also important to note how these disparate streams of imaginative religious purpose are amenable to visuality, to mediation. Powerful symbolic forms such as apocalypse; violent manly struggle; Biblical narratives such as the battle of Jericho; the Exodus story, and so forth provide plausible and widely-shared affective common ground. Systematically rendered in rhetoric, in social media and in formal media productions, they form the repertoire out of which networks, movements and interpretive communities can come together around seemingly common commitments. They are, as I have said, equivocal signs in that they need not be doctrinally or theologically or historically grounded to nonetheless be invoked and articulated into stark political purpose when the moment is right.

Recovered masculinities

A second dimension of these trends that is obvious in its searing material reality: that of masculinity and masculine purpose. Tropes, gestures, and memes of masculinity are all through the visual repertoire of the January 6 attack. A casual cruise through #capitolsiegereligion on twitter reveals an amazing array of such representations.

Much could be said, and is screamingly obvious, within the frame of traditionally-coded masculine gestures, attire, and equipage. More interesting, though, is a case like the “Q-Anon Shaman.” He is described, and describes himself, as located at some boundary between militia masculinism and a kind of “seeker”-like articulation with new-age and Aryan/Nordic traditions. Indeed, Christian identity is not alone in having experienced a resurgence of anti-state, individualist, identity impulses. This piece, shared with me by my colleague Monica Emerich, illustrates the extent to which even the “New Age” movement is subject to the same forces of emerging religious revanchism seen elsewhere. From that perspective, the “Q-Anon Shaman” represents a kind of trans-religious masculine figure.

I’ve already addressed some key dimensions of contemporary masculinity in an earlier post. There, I pointed to two characteristics of emerging masculine themes derived from my own research on religion and masculinity. First, I pointed to an under-appreciated dimension of masculinity, the question of masculine purpose. In our book Does God Make the Man?, Curtis Coats and I concluded that three things define masculinity in the main: Provision, Protection, and Purpose. The third of these is seemingly the most diffuse and ill-defined. We came to two conclusions about it. First, that most men we talked to (and I’d argue most of the men we are thinking about in contemporary religious politics) felt a deep need to have a sense of purpose. As we pointed out, though, most of them had difficulty specifying an object for that purpose. What would it be about? For most of them it took the form a longed for, unrequited desire. The second thing was that, for most of them, religion failed to provide them any persuasive sense of purpose that would satisfy that itch. Where they could find a sense of purpose, at least vicariously, was in media imaginaries of film, television, fiction, etc. So, it is sort of like there was this roiling inventory of unrequited purpose out there, just waiting to be tapped.

In my earlier post, I talked abut guns, boats, etc., as “technologies of masculine purpose.” These are things that are gendered. Men like to have them in part because there is a kind of implicit purpose in them. I suggested that with regard to guns and other weaponry, this inventory of such technologies had ominous potential. Well, we saw that potential realized at the capitol on January 6. And as much of the visual evidence would suggest, January 6 also resolved the other contradiction. Unlike the men we presented in our book, these men found a way to very much frame their purpose in religious terms. That roiling inventory of unrequited purpose found its expression in seditious action framed and legitimated by religion.

Media and mediations are integrated into this emergent masculinist religiosity in two ways. First, as I said, masculine purpose has always been an important theme of popular culture, from cowboy films to war films. Those media expressions, as well as the more seductive contexts of the social media, continue to provide rich imaginaries of masculinism.

Ornamental masculinity

A second mediation has to do with the way that contemporary masculinity is thought about and represented both conceptually and in material expression. In a fascinating discussion of masculinity in the Trump era, Susan Faludi has suggested that the dominant form of contemporary masculinism is what she calls “ornamental masculinity.” “Contemporary manliness is increasingly defined by display,” she notes.

Ornamental manhood is the machismo equivalent of “I’m not a doctor but I play one on TV.” Or, in the boogaloo movement’s version, “I’m not actually a soldier but I wear camo and walk around downtown with my big gun.” (In Mr. Trump’s case, it’s “I’m not a successful builder but I played one on ‘The Apprentice.’”)

Defining masculinity as “display” is suggestive in relation to the observation that much of the momentum of the events of January 6 seemed purposeless beyond a vague desire to invade and to steal-stop and to do real violence and damage. It was a revolution without a leader or an agenda, aside from a broad appeal by Trump to show strength. But, what it was was a throbbing multitude of unrequited masculine purpose, rising to and filling a religious and quasi-religious frame. And this is significant: media were important along several dimensions. First of course was all the evidence that it was in fact about display. All the selfies, the Instagram and Facebook posts, the posturing and preening and attire. It was almost defined by display.

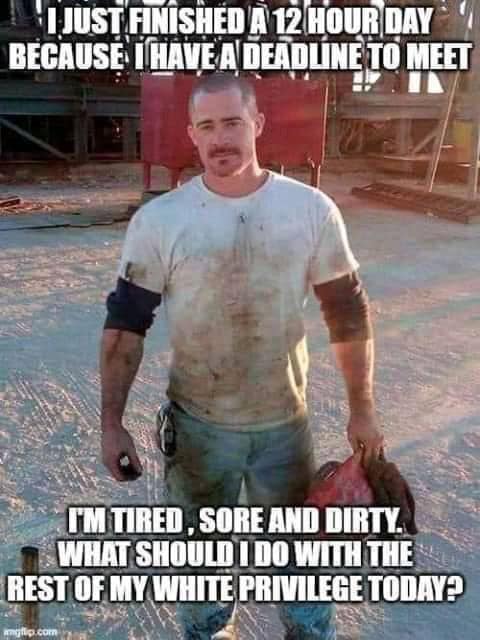

As a way of thinking about the question of ornamental masculinity, here is a meme I harvested from Facebook. We could spend a long time unpacking the politics of this image and its claim. But for my purposes here it is enough to note that it as visual argument fitted to a moment where the mediation of ornamental masculinity has achieved a certain level of cultural and material momentum. It is an image that knows what it wants and where it should be located the complex visual discourse of hypermediation.

This image is also evidence of my argument about media functioning as “affective infrastructures.” They provide structural/conceptual support for powerful and persuasive social forms and social movements. The media play their part and we as their patrons and circulators and communities, play our role. In the case of the events of January 6, we can see how a specific and increasingly important complex of social and cultural purpose is in fact an expression of and expressed through imaginative circulations made possible by the contemporary articulation between religion and media.

These are flexible, fungible, affordances of the digital age. They are complex and nuanced and layered. But, it is up to careful scholarship to unpack them. The specific cases of religion and politics in the Trump era and their expression on January 6 bring home that this is more than a project of intellectual curiosity. It might be of vital importance. I hope this series has made a start.

The roiling controversies of the past few weeks constitute a moment of social and political ferment in the U.S. Three things circulate; the ongoing covid pandemic; emergent cultural reckoning with racism; and a make-or-break general election. These are also of global import and significance as we’ve seen. The whole world is again watching.

The roiling controversies of the past few weeks constitute a moment of social and political ferment in the U.S. Three things circulate; the ongoing covid pandemic; emergent cultural reckoning with racism; and a make-or-break general election. These are also of global import and significance as we’ve seen. The whole world is again watching. n the same way it is for my colleagues-of-color. I take fully on board the words I’ve seen online saying this is not the time for White voices to come to the center. Not a time for “White-splaining.” But I have colleagues I care about who are saying that White voices need to say something. They are right. But the less the better. There will be plenty of time for cerebral reflection, post-mortems, and observations from our disciplinary perspectives.

n the same way it is for my colleagues-of-color. I take fully on board the words I’ve seen online saying this is not the time for White voices to come to the center. Not a time for “White-splaining.” But I have colleagues I care about who are saying that White voices need to say something. They are right. But the less the better. There will be plenty of time for cerebral reflection, post-mortems, and observations from our disciplinary perspectives. But in both cases, we can see an attempt to create a visual moment that seeks to cut through these contradictions by going straight for a position right at the center of some religious-social geography. What is that geography? Clearly the imagined religious-revanchism of social grievance advocated by a number of voices: Robert Barr, Mike Pompeo, Steve Bannon, and Trump’s own “evangelical cabinet” headed by Paula White.

But in both cases, we can see an attempt to create a visual moment that seeks to cut through these contradictions by going straight for a position right at the center of some religious-social geography. What is that geography? Clearly the imagined religious-revanchism of social grievance advocated by a number of voices: Robert Barr, Mike Pompeo, Steve Bannon, and Trump’s own “evangelical cabinet” headed by Paula White. again.

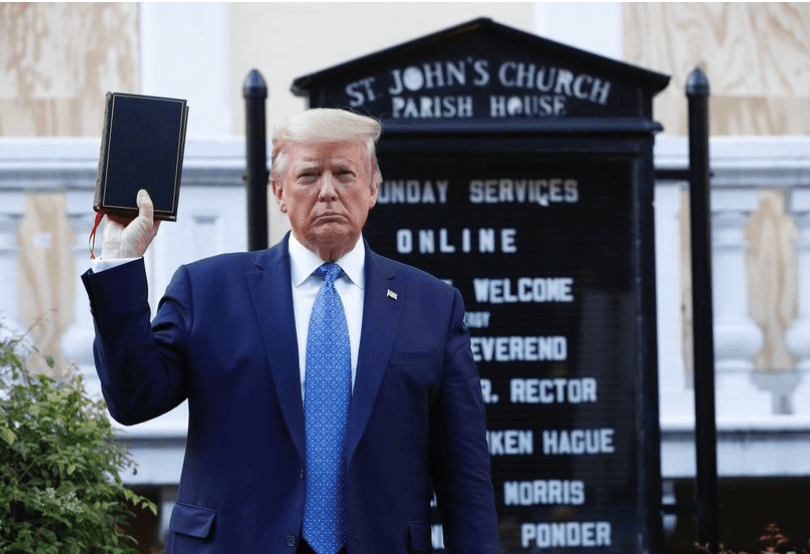

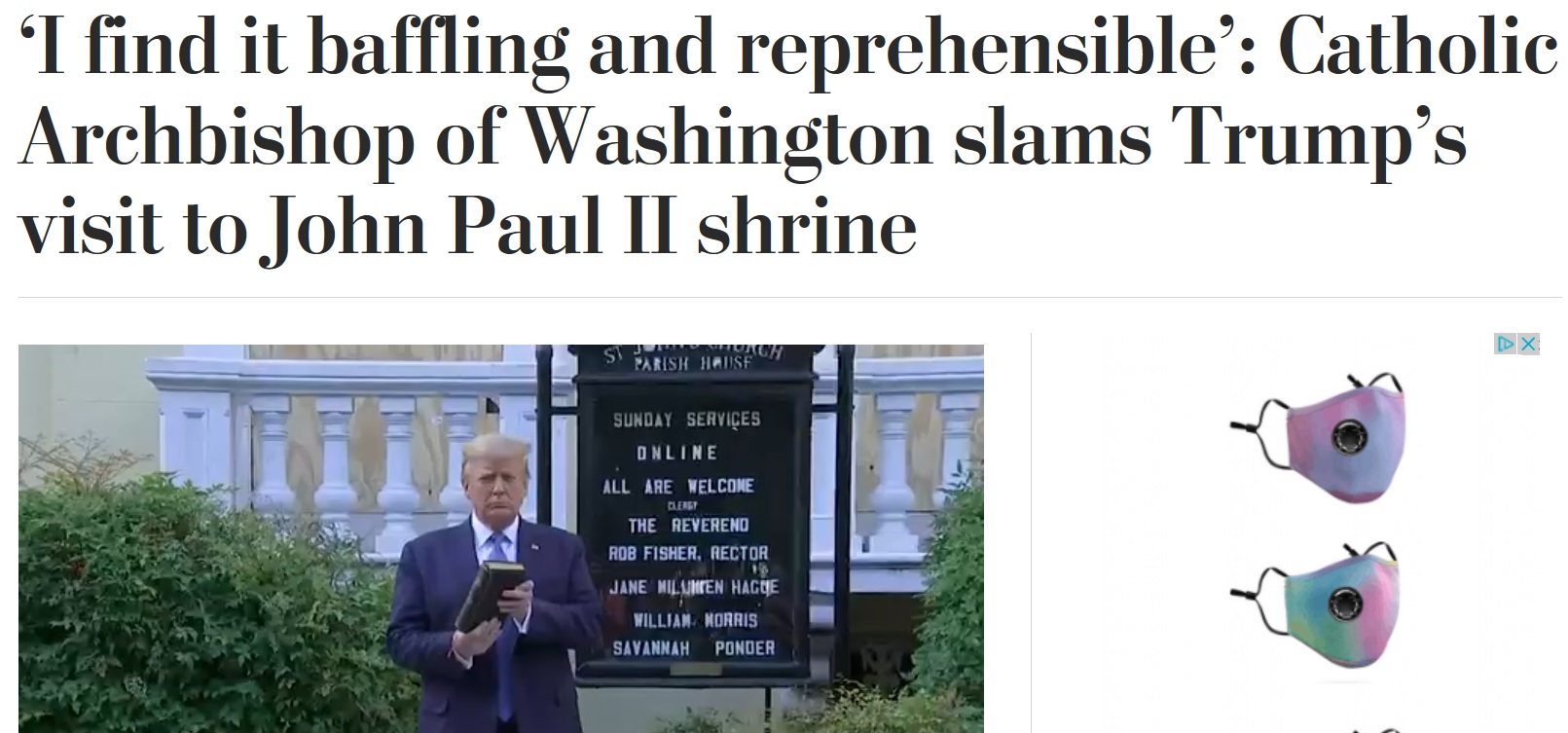

again. In the middle of all the chaos of late May and early June, 2020, no more chaotic image (in my view) circulated than one of Donald Trump holding a Bible in front of historic St. John’s church in Washington.

In the middle of all the chaos of late May and early June, 2020, no more chaotic image (in my view) circulated than one of Donald Trump holding a Bible in front of historic St. John’s church in Washington.